Other Meats On The Thanksgiving Table

One of the hallmarks of a feast in seventeenth century England and New England was the presence of several kinds of meat. The menus for the formal dinners of the wealthy might feature more than two-dozen kinds of meat. Even middle class people expected a nice dinner to feature a couple of varieties of meat. Undoubtedly, several meats were served at the 1621 celebration.

For large eighteenth and nineteenth century Thanksgiving gatherings, a single turkey hardly sufficed. Other meats filled out the menu, for example a roast of pork and a substantial chicken pie. In the mid 1800s in Stonington, Connecticut, Grace Denison Wheeler said about her childhood holiday dinner “the big turkey, brown and shining was accompanied by two big pans of chicken pie and roast pork, crisp and brown, clove studded so it had a spicy odor.” Since the holiday fell in the autumn butchering season, it was natural for farm families to have fresh pork on hand. Town dwellers who purchased their meat from butchers could have fresh meat more easily year round, and for them a chicken pie required a good deal less work than for the country dwelling folk, who would have to kill and pluck their own chickens before making a pie.

“Work With What You Got!”

© Victoria Hart Glavin Tiny New York Kitchen © 2015 All Rights Reserved

The Lunch Counter

Growing up in the 1960s going to the luncheonette (lunch counter) was a common lunchtime occurrence. These lunch counters were always in what was known as the “five and dime” store. My mother would take me shopping and we would stop at the lunch counter for a grilled cheese or egg salad sandwich. I would usually have an orange Nehi or a chocolate shake to go along with my lunch.

“Work With What You Got!”

© Victoria Hart Glavin Tiny New York Kitchen © 2015 All Rights Reserved

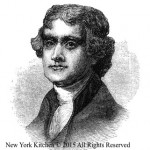

Another Culinary Debt To Thomas Jefferson 1789

Thomas Jefferson, then American minister plenipotentiary in Paris, asked a young friend visiting Naples to bring him back a macaroni machine. The young friend duly obliged, and the machine became the first of its kind in the United States of America when Jefferson returned home in September of 1789. It is unknown whether Jefferson followed the advice of the Parisian pasta maker, Paul-Jacques Malouin, who in 1767 had advised that, “the best lubricant for a pasta machine is a little oil mixed with boiled cow brains.”

“Work With What You Got!”

© Victoria Hart Glavin Tiny New York Kitchen © 2015 All Rights Reserved

Constitution Week – Foods of Our Forefathers Part VII

Constitution Week – Foods of Our Forefathers Part VII

Salting was also used extensively without intentional drying. In fact, salt pork, beef or fish (plus some cheese), was often the only animal protein available during the winter.

Salt was thus essential to the early settler. Although some was imported from Portugal and the West Indies, it was too expensive for general use. In some parts of the frontier, salt cost four times as much as beef, ad not until 1800 did it drop even to $2.50 per bushel. More modest households depended on “Bay Salt” produced along the coasts by the simple expedient of evaporating salt water from the ocean. Inland, however, it was another problem. There were occasional salt springs, but “licks” were more common sources, both for man and beast. Daniel Boone, in fact, owed much of his fame to his ability to find such salt licks on the frontier.

Except for large feasts, butchering was typically done in the fall, as soon as it was cold enough to chill the carcass rapidly. If a pig was butchered, a certain amount was reserved fresh, for immediate use, and some was made into sausage. Unless it was cold enough to be preserved in ice or frozen, the balance, especially the hams and side meat, was treated with salt containing saltpeter (potassium nitrate) and stored until it had lost considerable water. It was then exposed to hickory or fruitwood smoke for several days, and then hung in a ventilated shed or barn for months, as it gradually lost moisture. After some six to eighteen months, it had become what we know as a “country ham,” and contained from 3 to 7 percent salt.

When an animal was butchered in the summer or in milder weather, it was a different matter. Smoking, drying and “corning” (pickling) was very important, but if meat was to be used fresh, other precautions needed to be taken. If a householder had access to ice, the “roasting meat” could be kept safely for several days. If she wanted to keep it for a week or so, its surface was dried carefully with a towel and it was hung in the basement. First, however, it was sprinkled with salt and pepper, which discouraged flies, and also helped cover with inevitable taint.

For still longer storage, some cookbooks recommended that the roast be wrapped in cloth, laid in the coal bin, and covered with a shovelful of coal! The purpose of this treatment, other than to discourage flies, is unclear.

All parts of an animal were important to the early American housewife, including many the consumer tends to spurn now. Heads were used routinely in cooking, as were tongues, palates, and stomachs. Intestines, of course, were used for sausage casing and the fat was rendered for lard. Sausage was made from otherwise unappetizing but edible parts. Feet were the source of jelly, to be used later for thickening puddings such as blanc mange, and for soup.

In fact, frontier wives made an early version of “bouillon cubes” from such jelly. They would boil calves’ feet and other bones in water to extract the jelly, cool the solution, remove the fat and sediment, and then boil again to concentrate the solution. When sufficiently condensed, this would be cooled in a shallow pan, where it would solidify to be cut into strips. Dubbed “portable soup,” these strips could be carried on long trips, and dissolved in hot water to yield a tasty broth.

Unfortunately, although the settlers and woodsmen didn’t know it, the protein in this material was almost worthless nutritionally, except for its small caloric value.

Fruits and vegetables were the most difficult foodstuffs to provide off-season in anything approaching their natural state. Some, of course, were stored in the root cellar. A few were dried, like apples, especially in New England, but products like raisins and prune (from grapes and plums) required more sun and heat than were available in the north. Brining was a relatively simple way to preserve a variety of vegetables for moderate periods without drastically changing their flavor. Snap beans, carrots, cauliflower, celery, onions and sweet peppers were submerged in a mild salt-vinegar brine in a crock, where they could be kept several months.

More drastic pickling treatment was also used for cucumbers, cauliflower, carrots, and green tomatoes, to say nothing of shredded cabbage – sauerkraut. Beef was also pickled (or corned), as were certain fish such as herring.

Pickling had two primary nutritional effects on the material treated: it substantially increased the salt content of the foods involved, and drastically reduced their content of vitamins. Washed and sorted vegetables were laid in a crock in layers, and then covered with layers of salt. Sometimes grape leaves were also used in the intervening layers: their natural acids helped firm up the pickles, or alum was used for its greater dependability if it was available.

After the crock was full, a vinegar brine was poured over the whole, to cover the produce, and the whole thing weighted down with a plate and a stone.

One continuing problem was determining the strength of the vinegar. Most vinegar was homemade from blemished or insect-ridden apples and the concentration varied widely. Consequently, some batches of pickles spoiled because the acetic acid content of the vinegar was too low, while others were almost inedible because it was too high. The crock had to be tended daily during the first few weeks after “laying the pickles down,” to skim off the foam which would arise during the fermenting process. The brine was normally changed at least twice during the process also, before the pickles reached a stable condition and could be used or stored for later in the winter.

Sauerkraut, of course, is essentially fermented, pickled cabbage. It was commonly served in the northern part of the country as a vegetable during the winter months. The pickling process reduced its vitamin A and C content to about one-third of that present in freshly shredded cabbage. The cabbage stored in the root cellar also lost its vitamins, but not to the same degree.

Cucumber pickles lost a similar amount of these vitamins, leading to a very real risk of deficiency, diseases, especially scurvy. Fortunately, potatoes helped provide a substantial portion of vitamin C, and they stored well over the winter. Fortunately also, such crops as sweet potatoes and winter squash retained their carotene concentration during cool storage.

Sugar played an important part in food preservation in early America also, although it was a scarce commodity in colonial days. In the Northern colonies, honey and, to a lesser extent, maple syrup and sugar, were the “sweetnin” in the earliest days; refined sugar was imported from England and consequently expensive. Sugar cane, however, rapidly became a cash crop in the South, and plantation owners learned to process it into brown sugar and molasses. Plantation sugar was a highly variable product, and early American Cookbooks were full of warnings about clarifying the sugar before using it for the finest jellies and preserves. For the more elegant dishes, refined white sugar was specified. It was imported in cones weighting about ten pounds, and pieces were cut off with sugar shears as needed. The cones were wrapped in blue-dyed paper, and the innovative housewife often soaked these papers in water to extract the Indigo dye. The extract could be used to tint her homespun and other textile fibers.

There were several other related sweeteners as well. The best plantation sugar was the light brown product of the first boiling and crystallization. The wet crystals were put on trays to dry, in such a way that any “run off” could be trapped and bottled as “treacle.” This was usually the cheapest sweetener available to early Americans.

Water was added to the leftover syrup, the product was boiled again and a second batch of brown sugar was crystallized. This process was repeated several times, and the syrup left behind after the last boiling (usually the fourth or fifth) was blackstrap molasses. The sugar content was low, and the product contained significant amounts of minerals and impurities.

Sugar was used to preserve a variety of fruits for winter use. Fruit preserves, jam and jellies were common, of course, especially where berries were plentiful. The fruits were boiled with sugar in much the same procedure as it used today, and the bottles were sealed with beeswax or a mixture of candle wax and rosin. Or a piece of paper would be pasted to the top of the jar with egg white, and the whole piece then painted with egg white, using a feather for a brush. It was considered a good thing if a “leathery” mold formed on the surface, because it kept the air out. The mold was simply removed carefully prior to use.

Sugar was also used as a preservative in some meat preparations. Dried meat was pounded with fat, sugar and acid berries, such as blueberries, into a mush to make pemmican, which was then stuffed into a sausage casing. The sugar “tied up” the moisture so that bacteria couldn’t grow. The product kept for a month or more on frontier voyages. The principle is similar to that used in producing semi-moist pet foods today.

Corn syrup was unknown in early America, as were sugar beets, but other products were used as sweeteners. Sorghum was grown extensively for this purpose, especially in areas less tropical than Louisiana. Sorghum couldn’t be crystallized into a sugar, but the molasses served eminently well as a base for many dishes, and even as a source for alcoholic beverages.

It is difficult to determine how the diet of early Americans affected their general health. Obviously, in the warmer parts of the country, fresh fruits and vegetables provided plenty of vitamins and minerals even though the settlers didn’t know it. Plentiful game provided high quality protein, and the new corn was nutritionally beneficial.

However, even in the southern colonies, slaves and working people subsisted for long periods on corn bread, molasses and salt pork, a diet leading frequently to pellagra. On good plantations, the slaves might also get a ration of sweet potatoes, black-eyed peas, collard greens, salt fish in winter, and sometimes fresh beef. All excellent sources of needed vitamins, minerals and protein.

In the North, meals must have been very boring during much of the year. Foods that would keep were emphasized, with corn and cured or salt pork providing the backbone of the diet. Corn was served a hundred ways, from grits and hoe cake (so called because it was first cooked on a hoe held in a fire) for breakfast, to fresh corn, corn soup and cornbread, and desserts like Indian Pudding.

Vitamins would have been in short supply during the winter and spring. Almost all the preservation techniques (pickling and salting especially) drastically reduced the vitamin C and A contents of cucumbers, cabbage and meats. Carotene in fruits, such as were available, stood up pretty well to drying, and was available in stored vegetables such as sweet potatoes, winter squash and carrots. Scurvy was common, especially in the winter and on the frontier.

As America’s frontier moved west and the population increased, cities grew and flourished. At the time of the Revolution, the largest city was Philadelphia, at 40,000. In 1790, at the first census, the population of the entire country was less than 4 million, only 3 percent of whom lived in cities. As of today, (September 23, 2013), the US population is over 316 million.

Along with this change came gradual changes in the food supply. Where once each family fed itself, many now came to depend on others. Fast transportation developed, and new processes, such as canning, refrigeration and later freezing and controlled-atmosphere storage, came into growing use. Food could be produced where it grew best and shipped to the cities for consumption. Specialization aimed at lower cost and higher quality increased, and longer shelf life became more important.

Also, as the distance between food production and its consumption grew, new regulatory activities aimed at ensuring the wholesomeness and safety of the newly separated food supply also grew. This growth is a story in itself, but the process continues today (although there has been a movement to eat more local). America’s consumer knows that he or she can buy food in almost any form and at almost any level of convenience he or she chooses. In food, America’s bountiful heritage, the choice is the consumer’s whether it is from a farmers’ market or a supermarket.

Constitution Week – Foods of Our Forefathers Part VI

Drying was one of the major processes by which the colonists preserved the bulk of their winter’s stores. Fruits, especially apples, pears, peaches and apricots, some vegetables, and meat, particularly fish, were dried in large quantities for later use. Drying in the cloudy North was a tricky business, and was often combined with salting, especially for meat and fish. Even with salting, however, a rack of split, headless fish would have to be unloaded and stacked for overnight indoor storage to prevent the day’s drying from being “undone” by the evening damp. A string of cloudy, humid days was a threat to the whole process too, raising the possibility of loss by fermentation before drying had proceeded far enough to inhibit bacterial growth.

Drying had other problems too. Good air circulation on all sides was a must, and nets of hair were used to support the fruit or fish. The food being processed had to be turned frequently, several times a day during the early stages.

It also had to be protected from insects, bird droppings and blowing dirt, which was no mean task. Many early cookbooks carry explicit instructions to the housewife to examine her dried foodstuffs carefully, and to remove any portions, which were too heavily infested with insect eggs. A thorough cooking generally rendered the food safe, if not as esthetic as modern cooks might ask.

Since drying was such a time-consuming task, housewives often got together to do at least some of the work in company. Apple paring and coring parties were not unusual. After the apples were sliced, they were laid on screens or strung on strings to dry, after which they could be hung in the attic for use as needed. A bushel of apples yielded about 7 pounds of dried slices, which were especially welcome when rehydrated and made into “Schnitz Pie” or apple cobbler during the winter months.

If the housewife was especially concerned about appearance, she would sulfur her apples and other fruit as it dried. The trays of fruit slices would be stacked so as to allow air circulation, and the stack covered with a barrel or tight box, which was propped up off the floor about a half-inch. An ounce of “flowers of sulfur” was then twisted into a paper, set afire and stuck under the barrel for an hour’s exposure. The sulfur dioxide fumes acted both as a bleach and a preservation for the fruit.

Dried foods naturally lost a variety of nutrients during the process. The amount of nutrient loss varied with the skill of the housewife-processor, and with the weather and the sophistication of the equipment available to her. Fruits took longer to dry in the natural environment and hence lost some of their nutritive properties via spoilage and fermentation before the water concentration dropped to an appropriately low level. Conversely, if material were inserted in the brick oven after the day’s bread was baked, the temperature was sometimes excessive, and destructive to vitamins and delicate sugars.

Many housewives, however, learned the art very well, and produced dried fruits which would keep almost indefinitely, and which could be reconstituted months later to be used for stewed fruits, pies, and other dishes.

On interesting processed food invented by early Americans was hominy. As eaten, hominy was a winter substitute vegetable for sweet corn – although its vitamin C was completely destroyed, its vitamin A drastically reduced, and its protein content diminished. Still, it was available – provided the cook was willing to go through the long series of steps required in its preparation. First, a quart, say, of dry shelled field corn was boiled in a gallon of water containing an ounce of lye for about 30 minutes. This caustic solution was then drained off, the corn rinsed several times in fresh water, and then it was rubbed (under water) between the palms to remove the husks and black tips, which floated to the surface. The cleaned kernels were then covered with about an inch of fresh water and boiled for 5 minutes, drained, and covered again and boiled-flour times-and then boiled finally for some 45 minutes or until soft. It’s a small wonder the vitamins were lost!

To Be Continued…

Constitution Week – Foods of Our Forefathers Part III

Constitution Week – Foods of Our Forefathers Part III

The abundance of meat in America was a major change in the diet of the early settlers. Rabbits and squirrels were available year-round nearly everywhere, plus deer and other large game in many regions. As settlers moved west, buffalo gained importance in the diet. Fish, shellfish and wild fowl became common food, and they were all essentially “free.” The existence of these various forms of game was a literal life saver in times of uncertain crops and unbroken land. The game gradually diminished, of course, as the population expanded and settlers pushed west, but it provided a large share of the diet in early and frontier days.

Ham, of course, appeared on almost every settler’s table, rich or poor. It might be the only meat served at a meal or it might appear in company with more exotic roasts and fowl, but it was always there – breakfast, dinner and supper.

Corn was also a staple of the colonists, either fresh in summer, or as hominy or corn meal all year. Corn was also put to another use by an early Virginian, Captain George Thorpe, who may have been the first food technologist in America as he invented Bourbon whiskey shortly before he was massacred by the Indians in 1622.

Meal patterns for working people in rural early America were very different from those common today. Breakfast was usually early and light which consisted of bread, hominy grits, and sometimes fruit in season. Coffee, which was a new beverage at the time, was popular that is if it was available. A drink made from caramelized grain was sometimes substituted. Chicory was popular in the South, either alone or used to stretch the coffee. Tea was often made from local leaves such as sage, raspberry or dittany. Alcohol in some form was often served.

Breakfast in more elegant homes or large plantations might be later in the morning, and include thinly sliced roast and ham.

Dinner was served somewhere between midday and midafternoon, depending on the family’s circumstances, and was the big meal of the day. There was almost always ham, as well as greens (called sallat), cabbage and other vegetables. In the proper season, special dainties would appear – fresh fruits and berries, or fresh meat at appropriate butchering times.

Desserts could be simple such as a scooped out pumpkin, baked until done and then filled with milk, to be eaten right out of the shell. Or dessert could be more complex such as ice cream or other fruit flavored frozen pudding or a blanc mange. Blanc mange was prepared from milk and loaf sugar, flavored with a tablespoon or two of rosewater, thickened with a solution of isinglass (derived from fish bladder, soaked overnight in boiling water). This mixture was boiled for 15 to 20 minutes, then poured into molds to set.

If isinglass was not available (most was imported from England), homemade calves foot jelly could be substituted, but eh dessert was not as fine.

Various alcoholic beverages, including wines, applejack, “perry” (hard cider made from pears), or beer were commonly consumed.

In winter, peaches and other fruit disappeared from the dinner table, to be replaced by dishes made from stored apples and dried fruit of various sorts. Soups or broths also took their place. Milk grew scarce as cows “dried up” in the short days. Vegetables gradually decreased in variety as stored crops wilted.

Apples quickly became a staple in early America. Orchards were easy to start, required a minimum of care, and apples stored well. Housewives devised a multitude of “receipts,” including sauces and butters for off-season, as well as many using dried apples.

Supper was late and a light bread and butter, some of the left-over roast from dinner, fruit (fresh if in season, pickled and spiced otherwise), and coffee or tea.

To Be Continued…